6 Common Myths About Melatonin, Debunked

Just in the last year, there’s been a massive surge in the number of consumers buying melatonin to help with their sleep problems. But with that increase comes a lot of misinformation, too.

While Dr. Bo Martinsen and I don’t claim to be the ultimate melatonin experts, we have read several hundred research articles on the subject. And as physicians, our goal is to help guide you as to what makes sense – and what definitely doesn’t.

What Is Melatonin?

Found in almost every living organism on earth, melatonin is one of the most ubiquitous molecules in nature (1).

Technically classified as a hormone (just like vitamin D3), melatonin is partially emitted by a pea-sized organ in the brain called the pineal gland.

In a nutshell, melatonin is the hormone that regulates sleep, but there’s so much more to it:

One of its functions is to regulate our circadian rhythm by lowering brain temperature and boosting tiredness during periods of darkness. Thermoregulation, blood pressure, and glucose homeostasis are also regulated by this pineal hormone.

The Importance of Melatonin in the Modern World

Melatonin is secreted in the pineal gland in response to darkness. But in the age of bright screens, city lights, and frequent night work, we’re constantly disrupting the body’s natural production of melatonin. Even a few seconds of exposure to bright light at night can inhibit its secretion (2).

This is a major concern since our biological clock depends on light and darkness. It’s even estimated that about 10% of our genes are controlled by the circadian rhythm (3).

Bright light at nighttime inhibits melatonin secretion in the pineal gland.

Myth #1: Melatonin Use Is Dangerous Because It’s a Hormone

Although melatonin is classified as a hormone, it is not regulated by blood values (like testosterone or estrogen). Simply being in darkness or eating certain foods naturally increases the secretion of melatonin.

Refusing to take melatonin – just because it is classified as a hormone – doesn’t make much sense. If that were the case, there would be a long list of melatonin-containing foods to avoid, including fish, eggs, nuts, many kinds of vegetables and fruits, and even extra virgin olive oil (4).

With that said, there are some important questions about whether melatonin levels have a physiological effect on the sexual maturation of mammals.The impact of melatonin supplementation on the onset of puberty in people is still unclear. With just three limited studies on the topic to date, it’s hard to draw any conclusions at this time (5).

Myth #2: Long-Term Melatonin Use Is Detrimental to Health

A number of articles on the internet admonish against the long term use of melatonin, usually with some vague suggestion of the potential dangers.

So far, we haven’t been able to find any research that backs up these warnings. In fact, numerous studies and scientific reviews suggest quite the opposite:

• One 2016 review from researchers at the University of Copenhagen concluded, “No studies have indicated that exogenous melatonin should induce any serious adverse effects. Similarly, randomized clinical studies indicate that long-term melatonin treatment causes only mild adverse effects comparable to placebo (6).”

• A 2018 study on children and young adults found that, “Melatonin therapy sustained for 7.1 years does not result in substantial deviations of sleep quality as compared to controls and appears to be safe (7).”

• In a 2019 review of 50 melatonin studies, researchers concluded that, “Oral melatonin supplementation in humans has a generally favourable safety profile with some exceptions. Most adverse effects can likely be easily avoided or managed by dosing in accordance with natural circadian rhythms (8).”

• A 2020 study found that taking 2, 5, or 10 mg of melatonin per night was “safe and effective for long-term treatment in children and adolescents with ASD and insomnia.” This particular study had followed the children (ages 2 to 17) for two years (9).

• Perhaps one of the most persuasive statements on the safety of melatonin comes from Dr. Russel J. Reiter, Ph.D, M.D., one of the world’s foremost experts on melatonin. In one lecture, he comments “You cannot kill an animal or make an animal sick with too much melatonin. You can kill them with aspirin. You can kill them with any drug…You can’t do it with melatonin. The safety of melatonin over such a wide range of doses is very high.”

There is always more research to be done on long-term effects and especially in sensitive populations, like children, pregnant women, and the elderly. Based on the existing research, however, Bo and I have confidently used Omega Restore with either 3 or 5 mg of melatonin every night for the last four years.

Myth #3: Your Brain Will Become Desensitized to Melatonin

Unlike many prescription sleep medications – which may increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease – you are highly unlikely to become dependent on melatonin.

Researchers have consistently found that melatonin has a low rebound rate and no withdrawal symptoms, meaning that patients rarely experience adverse effects after they stop using it (10). Similarly, in the long-term 2018 study referenced above, researchers found that the sleep quality of children who discontinued melatonin use did not deviate from controls.

There are some studies that show melatonin may have a reduced effect on sleep parameters after 6-12 months of routine use. In these cases, simply taking a short break (or temporarily reducing your melatonin dosage) appears to improve effectiveness again (11).

More parents are giving children melatonin to combat sleep issues today.

Myth #4: Only People with Sleep Problems Need Melatonin

As we’ve tackled in previous articles, the role of melatonin extends far beyond sleep. Scientists are exploring melatonin’s impact on a wide range of conditions, including cancer therapy, aging, cardiovascular disease (12), anxiety and depression (13, 14), and neurological disorders like traumatic brain injuries (TBI), stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease (15).

There’s simply too much current melatonin research to highlight everything in a single article. We feel, however, that the effects of melatonin on the gut and aging brain are extremely important to address.

Melatonin and Gut Health

In 1958, Lerner et al discovered melatonin in the pineal gland. Years later, scientists also found melatonin in the retina, the human appendix, and then the gastrointestinal tract (16). If these discoveries had unfolded in the reverse order, however, we might be more familiar with melatonin as an important gut regulator today.

The gastrointestinal tract stores 400 times more melatonin than the pineal gland (17). Melatonin secretion in the gut is controlled by eating, as well as by the types of foods you eat.

In several clinical studies, melatonin supplementation routinely lessened abdominal pain in IBS patients (18). Melatonin has also been found to inhibit the spasmic effects of serotonin and relax smooth muscles in the GI tract as well as the reproductive, respiratory and circulatory systems (16). The result? Increased blood flow.

Intriguingly, studies also indicate that melatonin can reduce the GERD symptoms or heartburn cases affecting millions of Americans daily (19).

Research reveals that there is a strong connection between Alzheimer’s disease and low melatonin levels.

Melatonin and the Brain

Besides regulating our circadian rhythms, melatonin is one of nature’s best antioxidants, helping to protect the brain from oxidative stress through its action on MT3 receptors. Because of this antioxidant function, there has been a substantial amount of research on the neuroprotective benefits of melatonin (particularly for Alzheimer’s disease) over the last 20 years.

The body’s natural melatonin production dramatically decreases with age, and lower melatonin levels are considered a biomarker of aging. However, researchers have also found that Alzheimer’s patients typically have lower levels of melatonin compared to age-matched control subjects (20), leading to a suspected connection between the two.

In animal models of Alzheimer’s disease, researchers have found that melatonin may disrupt the production and accumulation of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, both hallmarks of the disease (20). More promising, some studies have demonstrated that melatonin slowed the progression of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer’s disease, and helped patients with Alzheimer’s disease and MCI improve their cognitive and emotional performance (20).

While melatonin supplementation may only be effective for patients in the earliest stages of AD, more than one recent scientific review has concluded that melatonin could be a helpful adjunct to Alzheimer’s disease therapy (20, 21, 22).

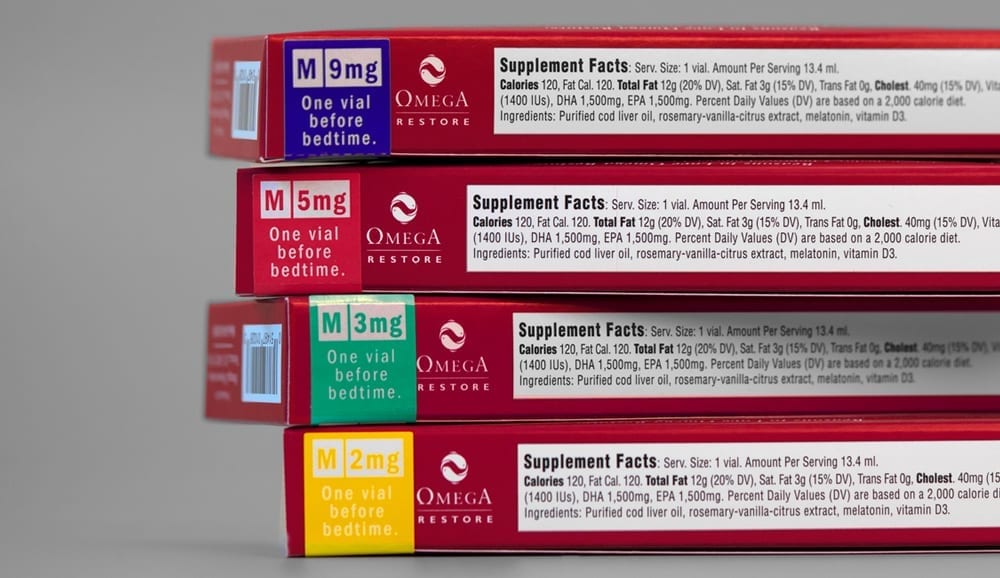

Myth #5: When Taking Melatonin, More Is Better

Research indicates that the effects of melatonin are dose dependent. In many cases, higher doses seem to provide better results, but that doesn’t mean that “more is always better.”

Because melatonin levels can be strongly influenced by genetics, age, diet, lifestyle, medication use, and more, the optimal dosage likely varies between individuals. A 9 mg dose that does wonders for your spouse may be too much for you (or vice versa).

The best way to determine your optimal melatonin dose is to simply try it out. Start with the lowest possible dose and work your way up. If you wake up frequently throughout the night – or experience unpleasantly vivid dreams – you might be taking too much.

A person’s optimal melatonin dose can depend on many factors, including age, genetics, lifestyle, medication use, and health condition.

Myth #6: Melatonin Doesn’t Work

When you delve into the research on melatonin, it’s easy to feel like you’ve discovered a miracle drug. At the same time, some people might wonder if melatonin is too good to be true – especially if they tried it once and didn’t notice an effect.

For the record, Bo and I do not believe that any single substance – whether that’s omega-3s, CBD or melatonin – is a panacea for everyone’s health problems. The human body is complicated and the path to good health usually involves a multi-pronged strategy including exercise, a balanced diet, good sleep routine, and healthy relationships and communities.

Just like with the research on so many drugs and supplements, the science surrounding melatonin is often conflicting. This doesn’t mean melatonin doesn’t work; it means that there’s more to understand about the impact of dose, individual differences, and how this molecule synergizes with other substances in the body.

How Melatonin and Omega-3 Fatty Acids Function Together

To focus on the question of potential synergies for a moment, Bo and I have spent the last five years exploring whether the effects of melatonin are enhanced by omega-3s. This is something we discovered when we started dissolving melatonin and vitamin D3 directly into our omega-3 oil. The combination in Omega Restore felt far more powerful than taking a melatonin pill, and hundreds of customers have reported similar results since then.

We believe that the effects of melatonin depend on the method of administration (ie. ingested as an oil instead of as a pill), and that the synergy between omega-3s, vitamin D3 and melatonin enhances the effects of all of them. These are topics we’re researching in partnership with independent scientists.

We’re excited to see where it leads us.

For More Restful Sleep and Energy

Experience the Omega3 Innovations difference for yourself with the most effective fish oil supplement on the market.

Buy Now

References:

1.Gaspar do Amaral, F. & Cipolla-Neto, J. (2018). A Brief Review About Melatonin, A Pineal Hormone. Archives of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 62 (4).

2. Reiter, R. J. (2017). Melatonin – Better Than Expected. University of Texas Health Science Center.

3. Xie, Y. et al (2019). New Insights Into the Circadian Rhythm and Its Related Diseases. Frontiers in Physiology, 10: 682.

4. Meng, X. et al (2017). Dietary Sources and Bioactivities of Melatonin. Nutrients, 9(4), 367.

5. Boafo, A., Greenham, S., Alenezi, S., Robillard, R., Pajer, K., Tavakoli, P., & De Koninck, J. (2019). Could Long-Term Administration of Melatonin to Prepubertal Children Affect Timing of Puberty? A Clinician’s Perspective. Nature and Science of Sleep, 11, 1–10.

6. Andersen, L. P., Gögenur, I., Rosenberg, J., & Reiter., R. J. (2016). The Safety of Melatonin in Humans. Clinical Drug Investigation, 36(3): 169-75.

7. Zwart, T. C., Smits, M. G., Egberts, T., Rademaker, C., & van Geijlswijk, I. M. (2018). Long-Term Melatonin Therapy for Adolescents and Young Adults with Chronic Sleep Onset Insomnia and Late Melatonin Onset: Evaluation of Sleep Quality, Chronotype, and Lifestyle Factors Compared to Age-Related Randomly Selected Population Cohorts. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 6(1), 23.

8. Foley, H. M. & Steel, A. E. (2019). Adverse Events Associated with Oral Administration of Melatonin: A Critical Systematic Review of Clinical Evidence. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 42: 65-81.

9. Malow, B. A. et al (2020). Sleep, Growth, and Puberty After Two Years of Prolonged-Release Melatonin in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.

10. Hajak, G., Lemme, K., & Zisapel, N. (2015). Lasting Treatment Effects in a Postmarketing Surveillance Study of Prolonged-Release Melatonin. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 30(1), 36–42.

11. Sparla, S., Koch, B. C., Bosma, R., & Nagtegaal, E. (2018). Recovery of Circadian Melatonin Rhythm After a Melatonin Holiday in Daytime Haemodialysis Patients on Long-Term Exogenous Melatonin. Functional Neurology, 33(4):188-193.

12. Sun, H., Gusdon, A. M., & Qu, S. (2016). Effects of Melatonin on Cardiovascular Diseases: Progress in the Past Year. Current Opinion in Lipidology, 27(4), 408–413.

13. Hansen, M. V., Halladin, N. L., Rosenberg, J., Gögenur, I., & Møller, A. M. (2015). Melatonin for Pre- and Postoperative Anxiety in Adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(4), CD009861.

14. Satyanarayanan, S.K., Su, H., Lin, Y. W., & Su, K. P. (2018). Circadian Rhythm and Melatonin in the Treatment of Depression. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 24(22): 2549-2555.

15. Alghamdi B. S. (2018). The Neuroprotective Role of Melatonin in Neurological Disorders. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 96(7), 1136–1149.

16. Bubenik, G. A. (2008). Thirty Four Years Since the Discovery of Gastrointestinal Melatonin. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 59 (2):33-51.

17. Chen, C. Q., Fichna, J., Bashashati, M., Li, Y. Y., & Storr, M. (2011). Distribution, Function and Physiological Role of Melatonin in the Lower Gut. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 17(34), 3888–3898.

18. Siah, K. T., Wong, R. K., & Ho, K. Y. (2014). Melatonin for the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(10), 2492–2498.

19. Majka, J. et al (2018). Melatonin in Prevention of the Sequence from Reflux Esophagitis to Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: Experimental and Clinical Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(7), 2033.

20. Shukla, M., Govitrapong, P., Boontem, P., Reiter, R. J., & Satayavivad, J. (2017). Mechanisms of Melatonin in Alleviating Alzheimer’s Disease. Current Neuropharmacology, 15(7), 1010–1031.

21. Shi, Y., Fang, Y. Y., Wei, Y. P., Jiang, Q., Zeng, P., Tang, N.,2, Lu, Y., & Tian, Q. (2018). Melatonin in Synaptic Impairments of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 63(3): 911-926.

22. Vincent, B. (2018). Protective Roles of Melatonin Against the Amyloid-Dependent Development of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Critical Review. Pharmacological Research, 134:223-237.

Popular posts

Related posts