Is Fish Oil Beneficial or Not? 9 Questions You Need to Ask

Omega-3 supplements have taken a publicity hit recently. In March, a much-cited JAMA meta-analysis found that omega-3 supplements provided no significant protection against “major vascular events.” And more recently, a study from the National Institute for Health (NIH) found that omega-3 supplements had no significant benefits for dry eyes compared to an olive oil placebo.

If you feel like you’re getting lots of confusing messages about the benefits of omega-3 fish oil, you are not alone. Omega-3 fatty acids are well researched nutrients, and every month, a crop of new studies, meta-analyses and scientific papers appear, discussing the effects of these fatty acids in cell biology and human medicine. While the majority of findings are positive, there are plenty of mixed results too, making it hard to know what to believe.

So what explains the conflicting data? And how can you tell what to make of a new study or article about fish oil? We encourage you to ask 9 questions as you analyze any piece of omega-3 research:

1. What EPA/DHA Dose Did the Researchers Use?

When it comes to omega-3 supplementation, dose is critical. This is true for all kinds of nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals. If you don’t take the right dose, you can’t expect to get spectacular results.

The omega-3 dose necessary to achieve results isn’t always straightforward, but there are strong indications of what works and what doesn’t. For instance, researchers examining the effects of omega-3 supplementation on rheumatoid arthritis write that they noticed symptomatic benefits with doses ranging from 2.6 g – 7.1 g per day, but saw “no effect” with 1 g per day (1). Similarly, in a heart health study, researchers saw reductions in blood pressure, stroke volume, and cardiac contractility with a 3400 mg EPA/DHA dose. At 850 mg EPA/DHA, these same benefits were not observed (2).

Researchers often report that the benefits of omega-3s are “dose dependent,” and that people need to get a certain threshold dose in order to achieve results. Numerous studies have concluded that the anti-inflammatory benefits of omega-3s don’t even kick in unless you consume at least 2000 mg daily (3, 4). And in studies examining the effects of omega-3 supplementation on blood pressure and triglyceride levels, the doses are more often in the 3000 – 4000 mg daily range.

A regular fish oil capsule contains only 300 mg EPA/DHA — a far cry from the 2000 – 3000 mg EPA/DHA dose you could get swallowing a tablespoon of cod liver oil or eating salmon for dinner.

Consuming higher omega-3 doses is especially important if you are like most Americans and eat a diet rich in pro-inflammatory omega-6s and mostly devoid of omega-3s. Because the omega-6s rival the omega-3s in the cell for same enzymes, you have to get enough omega-3s to balance out the fatty acid equation. And this takes far more than sprinkling a few chia seeds into your oatmeal.

In spite of the evidence suggesting higher doses of omega-3s are necessary to achieve measurable benefits, plenty of studies and meta-analyses use much lower doses. For instance, the recent JAMA meta-analysis included 10 studies with omega-3 doses ranging from a mere 226 – 1800 mg. Seven of those 10 studies used a very low dose, equivalent to eating just a few bites of salmon. It’s no wonder then that the meta-analysis also found that taking omega-3 supplements daily did not offer significant cardioprotection.

2. Did the Study Measure Bioavailability?

Even if you take a high dose of omega-3s in the form of supplements, you might not be getting as much as you think. That is because omega-3 supplements can be limited by bioavailability issues.

Several factors can hinder the bioavailability of an omega-3 supplement. For one, there’s the matter of how the omega-3 oil was processed and its resulting chemical form. For example, studies show that ethyl esters — a synthetic concentrate typically used in prescription omega-3 supplements — are less bioavailable than oils in their natural triglyceride form (5, 6). In addition, whether the omega-3 oil comes in a capsule, a liquid or a functional food also makes a difference. Numerous studies indicate that functional foods or liquids are better absorbed and/or achieve longer-term effects than capsules (7, 8, 9). Even how you take your omega-3 oil could make a difference. Some research suggests that taking omega-3 supplements in the morning with a low-fat meal could reduce bioavailability (10).

With all these variables, scientists have proposed one way to help determine bioavailability: Measure the amount of EPA and DHA fatty acids in the red blood cells. This measurement, also known as the Omega-3 Index, could make studies more reliable when reporting their results. An omega-3 index of at least 8%, which is the average level found in the Japanese population, is considered optimal (although Professor Bill Harris, who came up with the concept, now wonders whether a level of 10% might be better)(11).

Measuring bioavailability could aid our understanding of omega-3s’ heart health benefits, and could also help determine compliance rates. In addition, applying this standard could clarify existing data. As one scientist discussed, if one did a meta-analysis of clinical trials in which study participants reached an omega-3 index of at least 8%, the results would show that omega-3 supplements offered cardioprotection (12).

3. What Was the Source and Fatty Acid Makeup of the Oil?

When we think of omega-3 supplements, we generally think of “fish oil.” But as my fellow Omega3 Innovations co-founder, Dr. Bo Martinsen, discussed in a previous blog, fish oil could mean many things in today’s diverse market of omega-3 products. In the “fish oil” group, there’s salmon oil, cod liver oil, tuna oil, even shark oil…In addition, there are other kinds of omega-3 supplements stemming from algae, krill, octopus, and seal.

All of these sources contain different types of fatty acid makeups. For instance, a fish oil made from a blend of sardines, anchovies and herring, typically contains up to 30% EPA/DHA with more EPA than DHA and no vitamins. A typical cod liver oil contains 18 – 20% EPA/DHA with generally more DHA than EPA, plus vitamin A and D. A concentrated omega-3 oil could contain up to 90% EPA, without any DHA or other naturally occurring fatty acids at all. In addition, different fish oils contain large variations in saturated fat content.

Does it make sense to expect the same results from such different sources? I don’t think so — and some research indeed indicates that different fatty acid ratios could impact efficacy (13). In spite of this, the source and fatty acid makeup of an oil used in a particular study rarely get any attention.

4. How Was the Fish Oil Processed?

To further complicate matters, all omega-3 oils go through processing and purification. These steps can further change an oil’s nutritional makeup.

As discussed above, some oils are chemically manipulated into “ethyl esters” or “re-esterified triglycerides” — meaning the EPA or DHA level is artificially pumped up while the rest of the fatty acids and vitamins get removed. Ethyl esters are synthetic fatty acids, raising bioavailability and safety concerns (14), and should not be put in the same bucket with natural fish oils.

More common processing techniques can take their toll as well. For instance, Omega Cure® is a full-spectrum oil, meaning it has not gone through the normal “winterization process” almost all fish oils are put through. During winterization, an oil’s heavy acid layer gets skimmed away, removing potent fatty acids and nutrients in the process. Based on pilot studies and independent research, we’ve long believed that Omega Cure’s full-spectrum quality makes the oil more powerful than typical fish oils. But because few researchers have any knowledge of how fish oils are manufactured, these kinds of variables are largely ignored in the scientific literature.

Just like with extra virgin olive oil, how you process a fish oil will impact its nutritional value.

5. Did the Researchers Document Oxidation Levels?

Due to their numerous double bonds, omega-3 fatty acids are highly susceptible to oxidizing, or turning rancid. That is why fish and fish oil can easily smell and taste “off” if they’re old or prepared badly.

The problem is, when an omega-3 oil begins to oxidize, it not only smells and tastes bad; the fatty acids also break down into toxic byproducts that can harm your health. Unfortunately, because most omega-3 supplements are sold in capsules, the average consumer has no idea of the quality of the oil they are taking.

Independent studies from around the world have shown that the majority of omega-3 products on the market are rancid at the time of purchase, and a few scientists have been raising the alarm bells about rancidity. However, in spite of this issue getting a little more attention in the last two years, almost no studies report the oxidative status of their oils, even though these values are relatively easy to measure. This is particularly distressing since rancid, poor quality oil could very well explain the conflicting results we’ve seen in recent omega-3 studies (15, 16, 17).

As a separate note: It is important to remember that oxidation values are not fixed, but keep changing with time and depending on factors like storage conditions and exposure to oxygen. In studies, oxidation values need to be measured at the time of consumption, not 2 ½ years prior when the oil was initially developed.

Other Important Questions

Besides quality, source and dose issues, there are other — more standard scientific questions — that will impact the results of an omega-3 study too.

6. Compliance

Take compliance, for instance. Did the study participants adhere to research protocols, and if so, how was the compliance rate measured? Was it by counting the number of pills left over? Was it by asking the study participants if they complied and expecting to get a straight answer? Was it by measuring the omega-3 index?

7. Demographics

What type of participants were included in the study? Was the study conducted in the United States, Japan or India, where the average diets and baseline omega-3 indexes are radically different?

8. Time aspect

For how long were the participants followed? It typically takes 2 to 3 months before you start to see results with omega-3 supplementation, and another 12 months to see more gradual improvements for eye, heart, joint or brain health.

9. Type of Placebo

If a placebo was used in the study, what kind was it? For instance, the NIH dry eye study mentioned above used olive oil as its placebo. Since olive oil is a polyphenol-rich oil with its own active ingredients, it could have skewed results.

Remember: Omega-3s Are Complicated

The main point in all of this is that omega-3 supplementation is complex. We need to stop talking about ‘fish oil’ and omega-3s as though these are uniform substances.

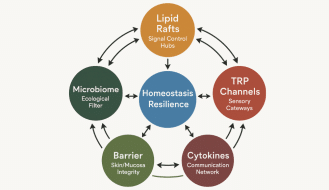

Omega-3 fatty acids are indisputably important for healthy cell functioning, helping regulate nutrient exchange, fighting inflammation, promoting cell signaling, and likely influencing gene expression. So if research shows that omega-3 supplements are working in one study, and then delivering no benefits in another, we need to take a closer look. We have to start asking “why?”

References:

1. Hill, C., Gilla, T., Appleton, S., Cleland, L.G., Taylor, A.W., and Adams, R.J. (2009).The Use of Fish Oil in the Community: Results of a Population-Based Study. Rheumatology (Oxford), 48(4):441-2.

2. Skulas-Ray, A. C., Kris-Etherton, P. M., Harris, W. S., and West, S. G. (2012). Effects of Marine-Derived Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Systemic Hemodynamics at Rest and During Stress: a Dose–Response Study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 44(3), 301–308.

3. Calder, P. C. (2013). Omega‐3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Inflammatory Processes: Nutrition or Pharmacology? British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 75(3), 645–662.

4. Fabian, C. J., Kimler, B. F., & Hursting, S. D. (2015). Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Breast Cancer Prevention and Survivorship. Breast Cancer Research : BCR, 17(1), 62.

5. Von Schacky, C. (2014). Omega-3 Index and Cardiovascular Health. Nutrients, 6(2), 799–814.

6. Dyerberg, J., Madsen, P., Moller, J.M., et al. (2010). Bioavailability of Marine N-3 Fatty Acid Formulations. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids, 83:137–141.

7. Köhler, A., Heinrich, J., and von Schacky, C. (2017). Bioavailability of Dietary Omega-3 Fatty Acids Added to a Variety of Sausages in Healthy Individuals. Nutrients, 19;9(6). pii: E629.

8. Watson, H. et al. (2017). A Randomised Trial of the Effect of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplements on the Human Intestinal Microbiota. Gut, pii: gutjnl-2017-314968.

9. Costantini, L., Molinari, R., Farinon, B., & Merendino, N. (2017). Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on the Gut Microbiota. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(12), 2645.

10. von Schacky, C. (2015). Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Cardiovascular Disease — An Uphill Battle. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 92:41-7.

11. Harris, W. (2018). Redefining Target Omega-3 Index Levels: The Japan Public Health Center Study. Atherosclerosis, 272: 216-218.

12. Meyer, B.J. and de Groot, R.H.M. (2017). Effects of Omega-3 Long Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplementation on Cardiovascular Mortality: The Importance of the Dose of DHA. Nutrients, 9(12), 1305.

13. VanderSluis, L., Mazurak, V.C., Damaraju, S., and Field, C.J. (2017). Determination of the Relative Efficacy of Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Docosahexaenoic Acid for Anti-Cancer Effects in Human Breast Cancer Models. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(12), 2607.

14. Opperman, M. and Benade, S. (2013). Analysis of the Omega-3 Fatty Acid Content of South African Fish Oil Supplements: A Follow-Up Study. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa, 24(8), 297–302.

15. Albert, B.B., Cameron-Smith, D., Hofman, P.L., and Cutfield, W.S. (2013). Oxidation of Marine Omega-3 Supplements and Human Health. BioMed Research International, 2013: 464921.

16. Cameron-Smith, D., Albert, B.B. and Cutfield, W.S. (2015). Fishing for Answers: Is Oxidation of Fish Oil Supplements a Problem? Journal of Nutritional Science, 4, e36.

17. Jackowski, S.A., Alvi, A.Z., Mirajkar, A., Imani, Z., Gamalevych, Y., Shaikh, N.A. and Jackowski, G. (2015). Oxidation Levels of North American Over-The-Counter N-3 (Omega-3) Supplements and the Influence of Supplement Formulation and Delivery Form on Evaluating Oxidative Safety. Journal of Nutritional Science, 4, e30.

Popular posts

Related posts